Recently, there have been two national observances here in the United States: July Fourth and the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg.

Where I live, a retirement community, the chapel’s electronic chimes played patriotic songs and military marches for more than a week in observance of Independence Day, with not even a break on Sundays out of respect for the Prince of Peace.

At Gettysburg, thousands dressed up in blue or gray uniforms to reenact a battle shot through with suicidal charges; a battle in a bloody war fought to save an institution that was itself soaked in blood drawn by millions of whiplashes.

Perhaps my responses to those observances would have been the same if I’d never met R. S. Thomas and read his poetry. But my thinking about chapel-chimed military marches is colored by his refusal to worship in cathedrals that have battle banners hanging from the rafters, and his attitude towards war in general tints my reaction to reenacting days of carnage.

Thomas warred against war: He was a pacifist. He also fought against himself: Was he a pacifist, he wondered, by conscience or by cowardice? Finally, he waged war against Englishheit: He threw himself into battle against the English-ification of Wales.

Thomas’s pacifism was not unlike that of numerous university students in the 1930s, but in the wake of the screeching Führer, many of them sloughed it off, arguing that this war was the lesser of two evils.

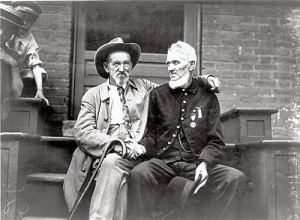

Thomas, however, remained a pacifist throughout his life, often expressing disdain for military types. Of a parishioner who was a retired officer, Thomas recalls: “And this one with his starched lip, / his medals.” In another poem, he describes generals “clanking / their medals.” Somewhere he refers to stuffed-shirts who made him aware that they had medals to clank even when the medals were not pinned to their chests.

Thomas, then, was an adamant pacifist, albeit one with an uneasy conscience. “Others were brave,” he writes. “Whether volunteering or conscripted, they went forth to the war, as their fellows had done hundreds of years.”

They acted.

“What does one do when one does not believe in action, or in certain kinds of action?” Thomas did not believe in the kind of action that would involve him in killing other human beings. But was his pacifism, he nagged himself, a matter of conscience or of cowardice?

He goes on: “Are the brave lacking in imagination?” Does he, Thomas, fail the bravery test, all because as a poet he can all too clearly imagine the carnage of war?

Is there, Thomas considered, a way to exhibit bravery other than by bearing arms? Courage in another cause? Perhaps by warring on the English-ification of Wales?

To state my case baldly: I suggest that Thomas fired searing words at England and the English as a way of showing that he, too, was brave.

I don’t think Thomas’s war was with individual English men and women, although who could blame them for taking his verbal knife-thrusts personally? His battle was with what he used “England” and “English” to stand for – Englishheit, English-ification.

These made-up words stand for the invasion of Wales by consumerism, by commodification – the measuring of all things in terms of buying power and salability.

Thomas watches young couples leaving the hill farms where the Welsh language and Welsh traditions have been preserved for centuries, and going off to English-speaking towns to draw pay-packets from English-owned factories turning out consumables for Londoners.

And so he launches poetic missiles at the English.

He sees English tourists coming to the beach at Aberdaron, the centuries-old port of embarkation for pilgrims sailing to the holy island of Bardsey. They come “All that way to eat ice-cream, to raise the newspaper as protection from the beauty of the sea.” Then, bellies bulging with potato chips and beer, they lurch at night from the pub to the cemetery of Thomas’s church to fornicate “to the tombstones’ rigid distaste.”

And so he launches poetic missiles at the English.

All the while Thomas is observing the depopulation of what were once the strongholds of Welshheit, the Welsh hills with their cottages in which the Welsh soul was nurtured for centuries. Those homesteads are going to ruin:

. . . and the smashed faces

Of the farms with the stone trickle

Of their tears down the hills’ side.

To a certain extent, the true Wales that Thomas was lamenting was a never-never Wales – an idealized Wales that he created to stand in opposition to all that he, a poet in the Romantic tradition, abhorred in modern industrialized, capitalist, technocratic society, a culture that he uses “England” and “English” to skewer.

As for Thomas, both of his wives were English, he sent his son to boarding school and university in England, and he depended upon English publishers and critics to gain for his poetry a worldwide readership.

Poems of R. S. Thomas quoted in this blog:

“And this one with his starched lip” – The Echoes Return Slow, 47.

“clanking / their medals” – “Not Blonde,” Mass for Hard Times, 24.

The prose quotes are from prose sections of The Echoes Return Slow, 20, 80.

“and the smashed faces” – “Reservoirs,” Not That Be Brought Flowers, 26.