One of my indelible memories: My son cradling his son in the crook of his arm, holding a book in his other hand, walking back and forth in the living room, reading Shakespeare aloud to a weeks’ old infant.

My grandson: Created by vocabulary?

A cautionary tale: In her recent mystery novel The Golden Egg, Donna Leon describes Venetian neighbors, many of them inveterate gossips, who are somewhat aware of a young man who never speaks, who hangs around a drycleaner’s shop and occasionally carries packages home for customers.

Then, the young man is found dead, and Commissario Brunetti begins to dig through multiple strata of untruths, quarter-truths, half-truths, and almost-truths, patiently piecing together Davide’s story.

After Davide was born, his mother shut him up in a room and didn’t speak to him. Never did he hear a voice, never learn a word.

Davide Cavanella: Not created by vocabulary?

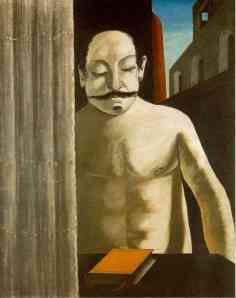

A work of art: During the First World War, Italian artist Giorgio de Chirico painted “The Child’s Brain.”

Looking at it, I see constricting interior space. A figure closed in by blank walls and heavy drapery. The sky squeezed between buildings, one of which has openings that are, with one exception, dark.

Looking at it, I see constricting interior space. A figure closed in by blank walls and heavy drapery. The sky squeezed between buildings, one of which has openings that are, with one exception, dark.

The figure, whose eyes are closed, is obsessed with his facial hair. His arms are spindly in comparison with his massive torso. There’s a table with a closed book; its placement suggests that if the man put it there, he had no intention of opening it.

The painting’s dominant colors are black and a grayish flesh tone. In the best reproductions, the book cover is a dull yellow, its marker is a ribbon of red to rhyme with the red adjacent to the sky’s blue.

The painting’s title is, to repeat, “The Child’s Brain,” from which we draw what conclusion?

The man has the brain of a child?

The painting is a metaphor for the brain of a child?

Or . . . ?

R. S. Thomas’s response is found in his book titled Ingrowing Thoughts.

Published in 1985, Ingrowing Thoughts contains poems triggered by Surrealist paintings that Thomas found in two books by Herbert Read: Art Now: An Introduction to the Theory of Modern Painting and Sculpture (first published in 1933) and Surrealism (1971).

Perhaps my favorite poem in Thomas’s book is his take on Picasso’s “Guernica.” More about that in a future blog, sometime after I’ve finished reading T. J. Clark’s new book Picasso and Truth: From Cubism to Guernica.

Back to Thomas’s reflection on “The Child’s Brain” by Giorgio de Chirico; R.S. spells it “di Chirico.”

The book is as closed

as the mind contemplating

it, vocabulary’s

navel in all that gross flesh.While the school reminds,

windowless at his left

shoulder, how you open

either of them at your own risk.

Thomas calls the building in the upper right-hand corner a windowless school.

“School” is his reading of the building, which is not, strictly speaking, “windowless.”

There are window openings in the walls, but they are glassless. Perhaps their panes were blown out by Taliban-like reactionaries who fear schools, in particular, schools for girls. Perhaps their window sashes were left to rot out by voters who chose to feed the wallets of the rich while starving the minds of the young.

It’s risky to open a book or a mind.

I know a young man who was homeschooled by a fundamentalist Christian and rockbound Republican mother. She took a risk . . . opening his mind. Now he’s organizing campaign offices for Democratic candidates.

Going back to the poem’s first stanza, we find the closed book identified as “vocabulary’s / navel.”

Without vocabulary, are humans simply gross flesh? Perhaps well-barbered gross flesh?

Is a book the navel through which vocabulary passes in order to nourish the gross flesh of a developing mind?

Is a brain simply gross flesh until vocabulary enters it?

Are humans created by vocabulary?

The book in de Chirico’s painting is facing us: It is there for us to open.

Poem of R. S. Thomas quoted in this blog:

“The book is as closed” – “The Child’s Brain – Giorgio di Chirico,” Ingrowing Thoughts, 29.