Between Here and Now, the title of one of R. S. Thomas’s books, announces a vagueness between two specifics.

“Here” indicates a specific location in space, the apartment in which I’m thinking and writing. “Now” points to a specific moment in time, 8:55 a.m., June 3, 2013, when my coffee has gone cold.

In the here and now, that’s something we understand. Thomas reports: “I take up apartments / In the here and now.”

But what can be between here and now?

Art.

Thomas uses the poems in Between Here and Now to nudge us toward that answer. The book, published in 1981, features thirty-three black-and-white reproductions of Impressionist paintings that were in the Louvre and now are in the Musée d’Orsay.

The paintings are presented in color in Germain Bazin’s volume Impressionist Paintings in the Louvre, where Thomas came upon them. As he looked at the works of such artists as Monet, Cézanne, Pissarro, and Van Gogh, Thomas formed poetic impressions of the artists’ painterly ones. With the result that there is a poem by Thomas to the right of each reproduced painting.

Following this first section titled “Impressions” is a second titled “Other Poems.” Two of these additional thirty poems contain the phrase “between here and now.” I quoted the first above; in the second, Thomas refers to “the interval between here and now.”

How does Thomas understand this interval? This vague break between two specifics?

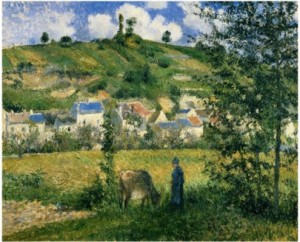

Perhaps his “impression” of Camille Pissarro’s “Landscape at Chaponval” opens the way to an answer:

It would be good to live

in this village with time

stationary and the clouds

going by. . . .

The village with its terracotta-tiled or gray-slated roofs is timeless. The woman waits quietly for the cow to munch her fill. While clouds sail by, and the wind ruffles grain, leaves, and grass.

Impressionist art, by its choice of pigments and use of brushstrokes, gives us a sense of both time stopped and time moving.

In another impression of a Pissarro painting, “Kitchen Garden, Trees in Bloom,” Thomas says that “Art is recuperation / from time.” One more Pissarro painting, “The Louveciennes Road,” moved him to speak of “exchanging / progress without a murmur / for the leisureliness of art.”

By visualizing an interval between here and now, art enables us to recuperate from the clock’s operations on our lives. It provides the leisure that allows us to gain impressions of something that somehow ‘exists’ in the gap between specific place and specific time.

In the penultimate poem in Between Here and Now, Thomas tell us:

. . . Art

is not life. It is not the rivercarrying us away, but the motionless

image of itself on a fast-

running surface with which life

tries constantly to keep up.

Those of us who have tidying-up minds, who want sentences to roll smoothly and logically from first word to final stop, may find those lines so convoluted that we close our eyes in despair.

Thomas hopes so.

For when our eyes are closed, we may receive impressions of a mysterious realm between here and now, a realm in which meanings that transcend the mundane slip into our consciousness.

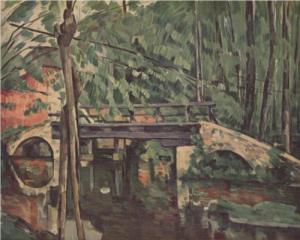

When I read the lines following “Art / is not life,” I recalled an earlier poem in Between Here and Now, Thomas’s impression of Paul Cézanne’s painting “The Bridge at Maincy.”

In his poem, Thomas wonders if Cézanne should have depicted someone crossing the bridge. After all, isn’t that what bridges are for? Yes, but this bridge is for us to look at and wait for a traveler to return to from the world of noise and activity. This bridge is for us to stop at long enough for the returnee to linger at the railing and wait for his face to emerge like a “water-lily” from the stream’s dark depths.

“Art / is not life.” “Art is recuperation / from time.” Art creates an interval of leisure between the place in which we’re stuck and the ticking clock.

In the poem in which Thomas declares that “Art / is not life,” Thomas sees a traveler always “Taking the next train / to the city, yet always returning / to his place on a bridge / over a river.” “So,” he continues,

will a poet

return to the work laidon one side and abandoned

for the voices summoning him

to the wrong tasks. Art

is not life. . . .

The task of the poet, the task of the painter, is not to create something that we can speed-see and speed-read and speed-comprehend. The task of the artist is not to officiate at “the marriage of plain fact with plain fact.”

Rather, the artist presides at the divorcing of facts, at the opening of gaps in the world that we call “real.” The artist creates an interval in which we catch glimpses of something that transcends reality, something that transforms the quotidian.

In art, we may sense a “stupendous presence” that no here and now is large enough to contain . . .

God.

Poems of R. S. Thomas quoted in this blog:

“I take up apartments” – “Flat,” Between Here and Now, 101.

“the interval between here and now” – “Pluperfect,” Between Here and Now, 89.

“It would be good to live” – “Pissarro: Landscape at Chaponval,” Between Here and Now, 45.

“Art is recuperation” – “Pissarro: Kitchen Garden, Trees in Bloom,” Between Here and Now, 41.

“exchanging / progress without a murmur” – “Pissarro: The Louveciennes Road,” Between Here and Now, 33.

“Art / is not life” – “Return,” Between Here and Now, 109.

“water-lily” – “Cézanne: The Bridge at Maincy, Between Here and Now, 49.

“the marriage of plain fact with plain fact” – “The New Mariner,” Between Here and Now, 99.

“stupendous presence” – Van Gogh: The Church at Auvers,” Between Here and Now, 65.