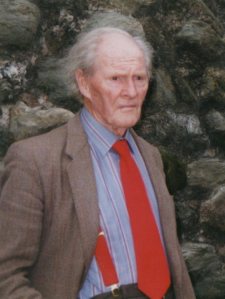

Today, the thirteenth anniversary of R. S. Thomas’s death, is a good time for reflecting on his legacy.

After my last visit with Thomas, in November of 1994, I drove on to his theological college, where I talked with the college’s head, John Rowlands, about how Thomas was viewed in Wales at large and in the Church in Wales, of which Thomas was a priest.

Rowlands said the general Welsh attitude was “Who will rid us of this turbulent priest?” While among his fellow churchmen, Thomas was often dismissed as eccentric and pessimistic, as a doom and gloom poet.

Speaking for himself, Rowlands compared Thomas to John the Baptist, saying that both men were voices crying out in the wilderness (Mark 1:3) of cultures that were under the heel of invading powers. In the case of John’s country, Palestine, the invader was Rome, whose officials worshiped the emperor as a god.

In the case of Thomas’s Wales, the invader was England, but England understood as a symbol for a culture dominated by technology, consumerism, and the worship of greed as a god.

Rowlands then said that Thomas was a prophet who was not without honor except in his own country (Mark 6:4).

Recently, during an interview on BBC’s HARDtalk, Richard Holloway, former Bishop of Edinburgh and Primus of the Scottish Episcopal Church, said that prophets are “awkward sods.”

For me, R. S. Thomas is an awkward sod for God – the preeminent religious poet of the twentieth and, I predict, the twenty-first centuries.

He speaks as a poet-prophet between two groups eager to be rid of him as a turbulent poet-priest. On the one side are unbelievers who refuse to hear him because he believes in God; on the other are believers who refuse to hear him because he often expresses doubts about God.

The first group, people more likely to read serious poetry, look for poets who do not bother them with God-talk.

This past Sunday, strolling along Nassau Street in Princeton, a magnet drew me into Labyrinth Books, where I stood delighted in front of the largest poetry selection I’ve seen for years. But not one book by R. S. Thomas.

I’m certain that if I were to stop in at one of the “Christian” bookstores in my area, I’d not find one book by R. S. Thomas.

Yet John Rowlands predicted, in 1994, that Thomas would be read for years to come. And I still agree.

I think there are soft edges of the two groups described above – edges that are breaking away and becoming spiritual pilgrims once more.

Thomas’s last parish, Saint Hywyn’s in Aberdaron, was an age-old pilgrimage destination – a tiny port where pilgrims boarded boats to carry them across a treacherous sound to the island of Bardsey, where, according to legend, the dust of twenty thousand saints is mingled with the soil.

Thomas refers to Bardsey in these lines:

There is an island there is no going

to but in a small boat the way

the saints went, travelling the gallery

of the frightened faces of

the long-drowned, . . .

Thomas made that treacherous boat trip many times while he lived in Aberdaron, but he questioned whether Bardsey would ever again attract pilgrims. In fact, however, the island and Saint Hywyn’s Church in Aberdaron are now doing just that, largely because of Thomas and his poetry.

But in one of his poems written while he lived in Aberdaron, Thomas places pilgrimage in a larger context:

. . . In cities that

have outgrown their promise people

are becoming pilgrims

again, if not to this place,[Aberdaron]

then to the recreation of it

in their own spirits. . . .

A growing number of people are, I think, becoming readers of Thomas’s poems, because a growing number of people are becoming unsatisfied with the thoughts of thinkers with final thoughts on both sides of the God-question.

These people of the middle way between doubt and belief are seekers at ease with endless seeking, for they know that not reaching a goal keeps them open to life’s suddenly moments – times when an unexpected revelation becomes, in Robert Frost’s words, “a momentary stay against confusion.”

For many persons in his day, Thomas may have been a prophet without honor in his own country, simply an awkward sod who sounded as if everything machine-like gave him heartburn; who gave atheists fits because he believed in God, and who gave theists fits because he often stormed at God “with the eloquence / of the abused heart.”

But for an increasing number of people, Thomas is an awkward sod for God, a poet-pilgrim leading other pilgrims who know . . .

It is too late to start

For destinations not of the heart.

Poems of R. S. Thomas quoted in this blog:

“There is an island there is no going” – “Pilgrimages,” Frequencies, 51.

“In cities that” – “The Moon in Lleyn,” Laboratories of the Spirit, 30-31.

“with the eloquence” – “At It,” Frequencies, 15.

“It is too late to start” – “Here,” Tares, 43.